Last week, I had a two-hour phone call with someone we will call B. Throughout the past eight months, I have spoken and met with B — who is a substantial part of my investigation into state-violence against environmental defenders — more than a dozen times, spending a few hours each time in heavy conversation. B has detailed the physical and psychological violence he has experienced and the effects of which he continues to grapple with today. As we were wrapping up our call, I decided to ask B a question that had been on my mind.

How are you feeling about the state of the world?

Personally, my outlook of the world has never been bleaker. Violence — against people and the planet — feels insurmountable. Nature is at the mercy of corporations. Lives have been deemed disposable. My colleagues, specifically journalists across Palestine and Lebanon, are being killed every goddamn day. (Yazan al-Zuweidi was the last journalist killed on January 14th). Meanwhile, many Western media outlets are failing to hold governments and corporations accountable for their role in these very atrocities. As a journalist — albeit a freelancer who does not answer to any one publication — it has been hard to see my future in an industry that is still struggling to plainly and honestly condemn the murders of more than a hundred of our own.

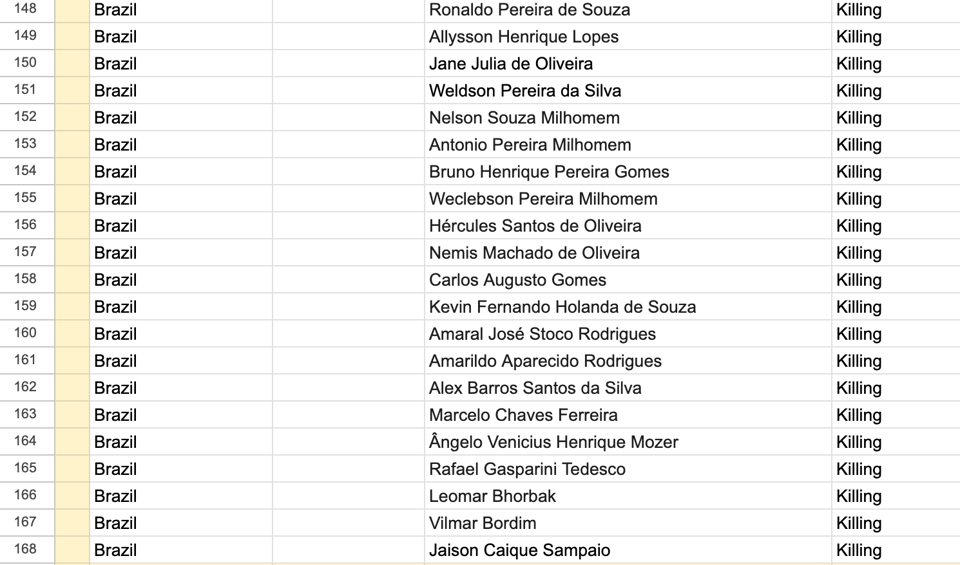

In the context of my work, I’ve also spent much of the past two weeks gathering data on cases of state violence against environmental defenders. I have a spreadsheet of more than 600 instances of intimidation, threats, arrests, injuries, and killings whereby the state has contributed in some way. (Because of my specific parameters, this is actually quite a short list compared to the total figures.) Often, it’s hard to pin down state force involvement but for the most part, governments create and benefit from the conditions that allow violence with impunity to flourish. In the broader context of paramilitaries with government links, politicians profiting from extractive industries, and decades of laws that undermine peasant rights and indigenous sovereignty, the state does not need to be directly involved because they are more or less always complicit.

This work has likely been driving my darker mental state as there is something a little grotesque, even if it’s necessary, about reducing brutality and those who have experienced it to rows, columns, and cells. Pair that with a few hours of gently prying into the thoughts and feelings of someone who has faced the worst of that brutality and the world is not feeling like such a great place.

Which brings me back to my conversation with B.

As soon as I asked the question, he didn’t hesitate to answer. “People come up to me at protests and say that I’m an inspiration to them,” he told me (B is among the most modest people I know and it was visibly uncomfortable for him to even mention this to me). “But what most people don’t know is that they inspire me.”

B went on to list the individuals, actions, and movements that he has seen, read about, or been part of and which show the strength and will of people to resist war, racism, exploitation, and environmental degradation. At progressive protests, during sit-ins, and through organizing events, is where he finds hope. The power of the people, he told me, should not be underestimated. It is why B is optimistic about the current and future state of the world. “How can I not be?” he said.

Last November, I witnessed B in the thick of this world while I was reporting from the San Francisco No 2 APEC protest. Despite the reasons people were gathered to protest —corporate greed, climate change, genocide — the intensity of life, of joy, was palpable. Most photographs I took include people singing, dancing, smiling, chanting. There is something infectious about resistance, about the collective act of demanding change.

In this light, there is a different way, a better way, of viewing my spreadsheet. It will always be a testimony to the violence we inflict upon one another in the name of capitalism. But to view it as nothing more is a disservice to those included. Every name in every cell is someone who has taken great personal risk to defend and protect ecosystems, animals, and communities from extractive industries, governments, “development” projects, and the tourism industry. Perhaps then, researching, documenting, and collating each person’s experience can be seen as a small sacred act, a way of acknowledging and thanking those who relentlessly face the bleakness, the cruelty, and the violence of the world and refuse to be crushed by the weight of its darkness.

Last year for Waging Nonviolence I spoke with Bre Joseph, a University of Massachusetts, Amherst senior and organizer with the campus chapter of Dissenters.

Dissenters is a grassroots, youth-led antiwar ovement that began with the mission to connect violence against Black and brown communities in the U.S. to the systems of oppression that fund, arm and enable global militarism. Since Oct. 7, Dissenters chapters have doubled down on antiwar organizing — holding local and national rallies, sit-ins, student walkouts and training events both on and offline. The UMass, Amherst campus chapter has organized protests, disruptions to sports games, and a sit-in at the chancellor’s office to pressure its university to cut ties with the weapons manufacturer Raytheon, now known as RTX.

Bre and I discussed organizing college students against weapons manufacturers, the radicalizing impact of activist arrests, and the lessons learned from successes and setbacks.

You can read the full Q&A here.

In early November at the No 2 APEC rally, I was standing near a Palestinian family — the dad and his two young boys pictured here — as they joined the protest to call for a ceasefire. On the stage in front of us, a roster of speakers discussed everything from workers rights and female activists under attack in the Philippines to the current siege of Gaza. Beside me, the dad hugged and played with his sons, both below ten years old, as they twirled their Palestine flags and passed a plastic bag of snacks back and forth. A friend joined the family and as the father turned to speak with him, I caught a glimpse of the boys’ signs. Handwritten in colored marker and crayon and surrounded by hearts, stars, and rainbows, each sign bore the inscription — 𝙎𝙩𝙤𝙥 𝙆𝙞𝙡𝙡𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙆𝙞𝙙𝙨 𝙞𝙣 𝙂𝙖𝙯𝙖. (Photo by Alessandra Bergamin)

Welcome back to my infrequent but no less beloved newsletter!

As I have in the past, I won’t promise a regular 2024 newsletter schedule. If it’s any consolation, the chaos of popping up in your inbox every so often is completely on-brand for me so… stay true to who you are.

In other news, I have been busy reporting and although I've shared very little of it — including a pretty big trip to the Philippines — I'll start to do so in the next few months. More and more I feel like social media has an ugly way of flattening everything into clickable, likeable, shareable bullshit. While I still participate in these platforms, in part because my work as a journalist and freelancer demands it, sometimes it's nice to keep significant things close to the vest for as long as possible. If you so wish, you can follow me here and here.

Rage On. ❤️🔥